We’re all busy, but busy doing what?

By Steve Walsh, Head of Jumping

If there is one thing most of us can agree on, it’s that we’re all rather busy.

Type that word – ‘busy’ – into a thesaurus and the first alternative you’ll come to is ‘occupied’, which is a good intersect to the point I’ll be trying to make in this piece:

- ‘Busy’ has connotations that what we’re busy doing is in some way important

- ‘Occupied’ by contrast strips those connotations away

Which is more accurate?

Are we busy carrying out important tasks that advance ourselves, our organisations and the people we work with, or are we merely occupied with what the day brings us?

A brief history of busyness

John Maynard Keynes, an economist so pioneering that he was named in Time magazine’s Most Important People of the Century in 1999, predicted in 1930 that economic growth would lead to us all working for only two days – 15 hours – per week within 100 years.

Keynes believed the greatest challenge we would face would be based less around how to fit everything into our work time, and more around what to do in the remaining 5 days per week.

Instead, as we approach Keynes’ prediction endpoint, we’ve completed a cultural 360: A study completed by the Institute for Social and Economic Research in 2005 concluded that “work, not leisure, is now the signifier of dominant social status… high human capital is now associated with longer hours of work”.

It’s no wonder then that we all associate with being busy – our social status depends on it.

You would think then, that all this extra time we’re spending working is significantly increasing our results. Well, not quite.

The problem with being busy

It’s now relatively well accepted that effort does not equal output.

Increased effort is closely matched to output to a relative peak point, at which we then hit diminishing returns and eventually start to reverse the positive effects of our increased effort, due to overload and burnout negatively affecting our performance as a whole.

Sport is well ahead of the curve on this one, and sportswomen and men have been practising the value of periodised training cycles for decades that feature periods of intense activity followed by lighter workloads that help produce peaks at just the right time, known as the supercompensation curve.

In our working lives though, we’re no closer to practising the value of intensity management than when Keynes made his prediction – we’re pretty much all on, or all off. 100mph every day until we’re so burned out that we need a week off. Repeat five times each year.

So, with the above in mind, why are we addicted to being busy?

The reason we love being busy

Completing tasks that are explorative, new, or have no defined end-point, such as research and development, can make us feel less productive than ticking off emails or writing reports.

Ironically, however, they are often way less important; the productivity-high we feel from completing 20 items on the to-do list isn’t equally returned in value when compared to a day working on strategic direction.

So why do we find it so difficult to detach ourselves from the productive in favour of the valuable?

The answer perhaps lies in research by the University of Chicago and Shanghai Jiaotong University, which identified that, “people who are busy are happier than people who are idle”.

Sitting thinking and brainstorming makes us feel idle and consequently makes us feel less happy.

How many times have you felt frustrated that you ‘haven’t got much done today’?

You may have come up with some of the most important ideas that will shape your team, department or business – but you can still feel unhappy with your output for the day.

Busy is holding us back

Following a study of 2,551 firms, Antonio Falato, Dalida Kadyrzhanova and Ugur Lel concluded in the Journal of Financial Economics that “directors’ busyness is detrimental to board monitoring quality and shareholder value”.

In other words, the busier the directors; the worse off the company.

Similar conclusions play out day after day in organisations large and small.

Directors, managers and senior teams spend large chunks of time being busy completing day to day tasks, and small amounts of time managing, directing and leading.

Organisations stand still. Change is a fantasy. Much gets done, at the same time as nothing much does.

How to break free from being busy

Breaking free from busyness isn’t a straightforward task – especially when our social status and happiness is rooted in being busy.

There are a myriad of time management ‘hacks’ that claim to help – from switching off emails to scheduling important tasks for first thing in the morning – but these don’t stop our busyness, they simply help us better manage the busyness.

Personally, there are two things I find helpful to stop falling into the busy trap:

1. Revisit your job description

I’ve found the number one way to eliminate busyness is to write down the most important single part of your job description, stick it to your desk or computer, and hold yourself to account by this, day in, day out.

If your job is to grow the company, then two-thirds of your day should be spent directly on activities that do just that, not on writing internal emails and reports.

If the reason why you were hired was to manage operations, then you can easily remember that you need to review and advance operations, not sit in meetings every day.

This is something Olympic Gold medallist Ben Hunt-Davies mastered when he wrote the book, ‘Will it make the boat go faster?’ – a book dedicated to his team’s singular focus.

If the proposal on the table could ultimately make the team’s boat go faster, it was in. If not, it was out. Simple.

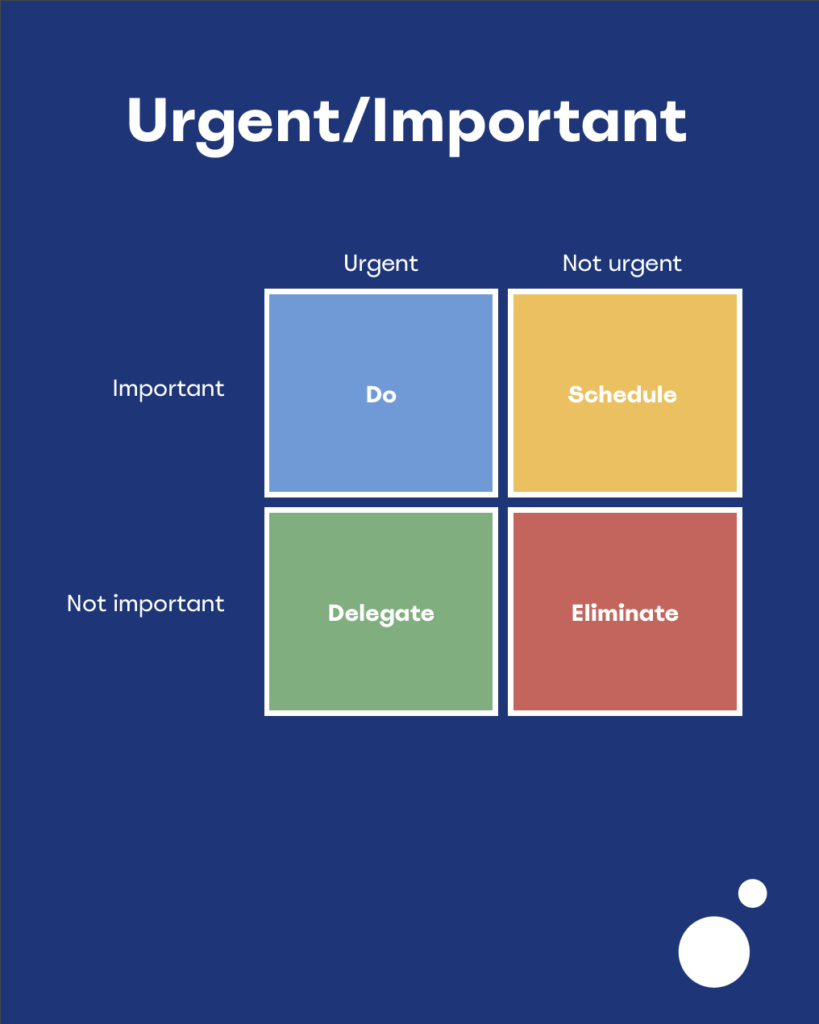

2. Master the Urgent-Important quadrant

Pioneering educator and author, Stephen Covey, proposed the Urgent-Important quadrant in his seminal book, ‘The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People’.

Covey is quoted as saying: “What is important is seldom urgent and what is urgent is seldom important,” giving the example that a ringing phone presents as urgent, but rarely is.

Use this as a guide to help you decide what’s important and aligned with your goals, and what’s simply presenting as urgent.

Start delivering impact and creating change

Research suggests that busyness is great for our social status and happiness, but not necessarily for our productivity or success.

The key, therefore, to curing our busyness addiction is to first change our mindset as to what how we perceive the former, so we can achieve the latter.

It’s time to ask ourselves: We’re all busy, but busy doing what?